The Bedtime Conversation That Changed How We Talk About Worries

Bedtime is supposed to be the quiet part of parenting, the gentle landing at the end of the day where everyone is soft and sleepy and grateful. In our house, bedtime is more like an airport at peak travel season, meaning somebody is always looking for something they suddenly cannot live without, somebody is negotiating…

Bedtime is supposed to be the quiet part of parenting, the gentle landing at the end of the day where everyone is soft and sleepy and grateful. In our house, bedtime is more like an airport at peak travel season, meaning somebody is always looking for something they suddenly cannot live without, somebody is negotiating terms like a tiny lawyer, and somebody is staring at the ceiling with thoughts that get louder the moment the lights go dim.

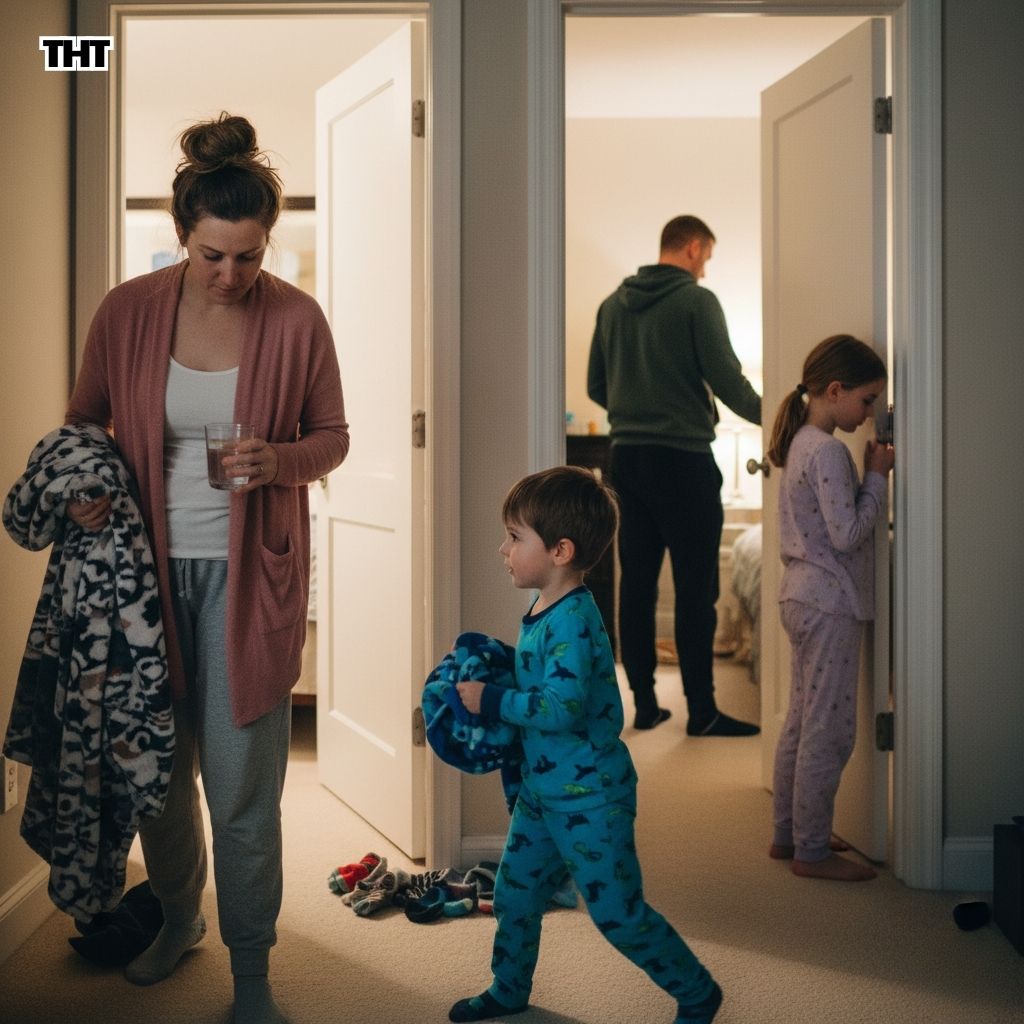

That night started like most nights start for us. Miles, six and full of restless energy, had invented a new reason he could not possibly go to sleep yet, which was that his blanket “felt wrong,” a complaint that sounded ridiculous until you watched him try to settle and realized his body truly could not relax. Nora, sensitive in a way that makes her deeply kind and also deeply prone to “what if” spirals, was quiet in the hallway, moving slowly as if the day had left a film of worry on her shoulders. Chris, calm and practical, was doing his usual final loop through the house, checking locks, turning off lights, fixing something small because his brain likes to end the day with a solved problem.

I was trying to keep my own tone steady, because I’ve learned that bedtime amplifies whatever emotional frequency the adults bring into the room. If I’m rushed, the kids feel it. If I’m short, they tighten. If I’m calm, it doesn’t magically make them calm, but it gives their nervous systems something to lean on.

We got Miles into bed first, because if you can get the loud one down, the whole house feels quieter by default. He asked for water. Then he asked for a different cup. Then he asked if water could go “stale” overnight and whether that would make him sick, which is how you can tell he has inherited Nora’s imagination in a slightly more chaotic form. I answered his questions, kissed his forehead, and walked out slowly, because a fast exit makes him feel abandoned, and he will call you back in with the urgency of someone who believes you are leaving forever.

Then it was Nora’s turn.

She was already in her room, sitting on her bed with her pajamas on, hair brushed, everything technically done, yet her body didn’t look done. Her hands were folded too tightly in her lap. Her eyes kept flicking toward the window. She smiled at me, but it was the polite kind of smile she uses when she’s trying not to be a “problem.”

I sat beside her and said, “Hey. You seem like you’re holding something.”

She shrugged, which is Nora’s way of admitting the truth without stepping fully into it. Then she said, very quietly, “I keep thinking about tomorrow.”

That sentence could have meant anything, and in the past, I would have been tempted to respond with the classic parent reassurance that comes out automatically, the one that sounds kind but often lands flat.

You’ll be fine.

Don’t worry.

It’s going to be okay.

Those sentences are not wrong, but they also don’t give an anxious kid anything to do with their worry. They’re like telling someone standing in the rain that the weather is nice. It might be true eventually, but it doesn’t help them in the moment.

So instead of trying to erase her worry, I tried to understand it.

I said, “What part of tomorrow is your brain stuck on?”

Nora swallowed, then said, “What if I forget my project. What if I mess up the presentation. What if people laugh. What if I cry.”

The last part came out fast, like she had been holding it in and it finally escaped.

That was the moment I realized we weren’t just dealing with a school project. We were dealing with Nora’s whole pattern, the way her brain tries to protect her by imagining every possible danger, then rehearsing the worst outcomes like they are facts.

And if I’m honest, we were also dealing with my pattern, which is that I love solving problems, and anxiety is not solved like a problem. It’s soothed, held, and gradually retrained through experience.

I took a breath and said, “Okay. I’m going to tell you something, and it might sound strange, but I think it will help.”

Nora looked at me, wary but hopeful.

I said, “We’re not going to talk about worries in the way we usually do, where they show up like a storm and we either try to stop them or we get swept away. We’re going to do something different. We’re going to treat worries like messages.”

Nora blinked. “Messages from who?”

I smiled, because kids always want a character, and honestly, it helps.

“Messages from your Worry Brain,” I said. “It thinks it’s a bodyguard. It sends alerts. Sometimes the alerts are useful. Sometimes it’s like a smoke alarm that goes off because you made toast.”

That made her snort a tiny laugh, which was a good sign, because humor is one of the fastest ways to loosen fear without dismissing it.

Then I said, “Here’s the new rule I want us to try. We don’t argue with worries. We don’t shove them away. We also don’t treat them like they’re in charge. We listen, we name what they want, and then we choose what we do next.”

Nora’s eyes narrowed the way they do when she’s thinking hard. “How?”

And that’s when the bedtime conversation shifted from comfort to skill, in the best possible way.

The Three-Part Conversation That Changed Everything

I didn’t plan this framework ahead of time. It came out because I needed something concrete, something Nora could hold onto when her thoughts got slippery and loud.

I said, “We’re going to do three steps. Name it. Thank it. Answer it.”

Nora stared at me like I had invented a new sport.

“Name it,” I explained, “means we say what the worry is, in one sentence, without adding five more scary sentences.”

Nora nodded slowly.

“Thank it,” I continued, “means we remember that your brain is trying to protect you, even if it’s being dramatic. We say, ‘Thanks, Worry Brain. I see you.’”

Nora made a face. “That sounds weird.”

“It is weird,” I said. “But weird works sometimes.”

“And ‘Answer it’ means we respond with something true and helpful,” I said, “not a guarantee, not a magical promise, just a steady answer.”

Then I asked, “Want to try it with the biggest worry first?”

Nora hesitated, then whispered, “What if I mess up the presentation.”

I said, “Okay. Step one, name it.”

She repeated, “What if I mess up the presentation.”

“Step two, thank it,” I said.

She sighed, then said, “Thanks, Worry Brain. You’re trying to protect me.”

“Step three, answer it,” I said. “What’s a steady answer?”

Nora went quiet again, because this part was the hard part. Anxious kids often swing between extremes, either everything will be perfect or everything will be horrible, and steady answers live in the middle.

So I helped her find the middle.

I said, “Could the answer be something like, ‘I might make a mistake, and I can still finish’?”

Nora considered it, then nodded. “I might make a mistake and I can still finish.”

I said, “That’s a strong answer.”

Her shoulders dropped slightly, almost like her body had been holding a brace and finally loosened it.

Then she said, “What if people laugh?”

“Name it,” I said.

She did.

“Thank it,” I prompted.

She did, with slightly less resistance this time.

“Answer it,” I said.

Nora chewed on her lip. “If people laugh, it might not be about me. And if it is about me, I can look at the teacher.”

I paused, impressed. “That’s very practical.”

She nodded, then added, “Or I can keep going.”

“Yes,” I said, “because continuing is a superpower.”

We went through several worries like this, and something fascinating happened. The worries didn’t disappear, but they stopped multiplying. Naming them in one sentence kept them from becoming a whole scary movie in her head. Thanking them kept Nora from feeling ashamed that she was worried at all. Answering them gave her a way to respond that wasn’t denial and wasn’t panic.

It felt like watching her take her hands off the steering wheel of fear and place them on something steadier.

The Part That Changed How We Talk in Our House

After we did a few rounds, Nora looked at me and said, “So you’re not going to tell me to stop worrying.”

It wasn’t accusatory. It was almost relieved.

I said, “No. Because you can’t stop a feeling by being told to stop. Also, your worries are not bad. They’re just loud sometimes.”

Then I added the line that became a turning point in our family language.

I said, “Worries can ride in the car, but they don’t get to drive.”

Nora smiled, because that made instant sense. She loves metaphors when they’re practical, when they make a situation feel manageable instead of mysterious.

She repeated it quietly, like she was testing how it felt in her mouth. “Worries can ride in the car, but they don’t get to drive.”

The next morning, when Miles panicked because he couldn’t find a specific toy he wanted to bring in the car, I heard Nora say something to him that made me freeze mid-coffee.

She said, “It’s okay if you’re worried. Worry can ride in the car, but it doesn’t drive. We can look for it for two minutes, then we go.”

Miles stared at her like she had become a tiny bedtime philosopher, but he actually followed her plan, because older siblings have power in a way parents never do.

I looked at Chris over the kids’ heads, and he gave me that small, pleased smile that says, this is working.

Why This Worked Better Than Reassurance

That bedtime conversation changed our “worry talk” because it didn’t treat worry like an enemy. It treated worry like information, and it offered a simple method for what to do when worry shows up.

Reassurance often fails anxious kids because reassurance asks them to accept something they cannot prove. “Everything will be fine” is a nice thought, but a worried brain will immediately respond, Are you sure? What if you’re wrong?

A steady answer, on the other hand, doesn’t need to be perfect. It needs to be usable.

“I might make a mistake and still finish.”

“I can look at the teacher.”

“I can take a breath and keep going.”

“I can try again.”

Those statements don’t promise a painless life. They promise capability, and capability is what calms anxiety long term.

The Positive Value We Took From It

In the weeks after that conversation, we started practicing a new habit in our family, one that has helped both kids in different ways, and honestly has helped me too, because adults have worry brains as well, we just dress them up in more sophisticated language.

We started separating the worry from the kid

Instead of saying, “You’re being worried,” we say, “Your worry brain is sending alerts.” That small change keeps worry from becoming identity, especially for a child like Nora who can internalize feelings as traits.

We started using “one sentence worries”

When worry shows up, we try to keep it to one sentence, because worry loves to sprawl. Containing it helps.

We started answering worries with “true and helpful”

Not “everything is fine,” but “here’s what you can do if it’s hard.”

We started practicing during calm times

The biggest shift was realizing that worry tools have to be practiced when the brain is calm, not only when it’s flooded. We started doing quick “name, thank, answer” practice during normal moments, like when we were packing bags or planning the next day.

Here’s the Part I Messed Up, So You Don’t Have To

I used to rush straight into fixing, especially at bedtime, because bedtime makes parents desperate for closure. If your child starts confessing fears at 8:43 p.m., your whole body wants to make it stop, because you can see your evening evaporating in real time.

But rushing creates pressure, and pressure makes worry louder.

That night, the reason it worked was because I stayed. I treated the conversation like it mattered. I let it take ten minutes longer than I wanted, and those ten minutes saved us hours of spiraling later.

If you try this, resist the urge to speed-run your child’s feelings. The goal is not to finish the conversation. The goal is to help your child feel more capable inside the feeling.

Final Thoughts

That bedtime conversation didn’t erase Nora’s anxiety, because anxiety doesn’t disappear because you had one good talk. What it did do was give us a shared language, a shared method, and a shared sense that worries are something we can face together without fear taking over the whole house.

Now, when Nora says, “What if,” I don’t feel the same panic rise in me, the panic that says I must fix this immediately. I feel steadier, because I know we have steps.

We can name it, thank it, answer it.

Worry can ride in the car, but it doesn’t get to drive.

And on the nights when the thoughts still show up loud, when the dark makes everything feel bigger, I sit beside her the way I did that first night, and I remind her of the best truth we found together.

You don’t have to get rid of worry to live your life.

You just have to learn how to keep going while it rides quietly in the back seat.