Why I Stopped Correcting My Daughter During Homework and Sat Beside Her Instead

For a long time, homework in our house had a familiar storyline. Nora would sit down with her pencil and her serious little face, I would sit across from her with my well-meaning “I can help” energy, and within ten minutes we’d both be tense in a way that made no sense for a third-grade…

For a long time, homework in our house had a familiar storyline. Nora would sit down with her pencil and her serious little face, I would sit across from her with my well-meaning “I can help” energy, and within ten minutes we’d both be tense in a way that made no sense for a third-grade worksheet.

It wasn’t dramatic every time, but it was consistent. It was the slow kind of stress that builds like static. I would correct her. She would tighten. I would explain. She would get quieter. I would say something like, “No, try it this way,” and she would stare at the paper like it had personally insulted her.

I knew I wasn’t trying to be harsh. I was trying to help. I was trying to keep her from making mistakes. I was trying to make it easier.

But one evening, after a homework session that ended with Nora blinking back tears over a math problem and me feeling like I’d accidentally stepped on her confidence, I realized something that changed the way I show up for her.

My correcting wasn’t helping her learn. It was teaching her that being wrong was dangerous.

So I stopped correcting her in the middle of homework.

I started sitting beside her instead.

And the difference wasn’t just better homework. The difference was a calmer child, a steadier parent, and a relationship that felt safer during hard things.

The Homework Scene That Made Me Finally Notice What I Was Doing

It was a Tuesday, which in our house is the most Tuesday kind of day. Chris was still working, Miles was in the living room building something loud, Juniper was asleep near the heater like she pays rent by napping, and I was trying to get dinner started while also being available for homework help.

Nora came to the table with her worksheet and said, “I don’t get it.”

It was a set of math word problems, the kind where the math itself is not terrible, but the wording makes kids feel like they’re decoding an ancient scroll.

She read the first problem out loud. Halfway through, she stopped and said, “Wait, what does it want?”

I leaned in and said, “Okay, so what you do is—”

And before I even finished explaining, she sighed.

Not a dramatic sigh. A quiet one. The kind that says, I’m already behind and now I’m going to be wrong in front of you.

She started writing numbers down quickly, like she was trying to get through it before I could comment. She picked the wrong operation. I corrected her immediately, because I’m a parent and my brain loves efficiency.

“No, that’s subtraction, not addition,” I said.

Her pencil froze mid-air.

Her shoulders rose.

She erased hard enough that the paper started thinning.

Then she whispered, “I hate math.”

And that’s when I saw what I had been missing.

Homework wasn’t a learning moment. It was a performance moment.

Nora wasn’t doing math. She was trying not to disappoint me.

That realization made me feel sick in the quiet way, because it wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted her to feel supported. I wanted her to feel capable. I wanted her to feel like mistakes were normal.

Instead, my constant correcting was making her feel watched.

Why Correcting Felt Like Help, But Wasn’t

Correcting is such an easy habit to fall into, especially if you’re a parent who cares. When your kid is working on something, you can see the wrong answer before they even finish writing it, and your whole body wants to save them. You want to protect them from frustration. You want to protect them from being wrong. You want to protect them from tears.

But here’s the problem.

When you correct a child too quickly, the message isn’t “I’m helping you.” The message becomes “You can’t trust yourself.”

For Nora, who already leans toward perfectionism, my correcting was like turning up the pressure. It made every mistake feel bigger. It made her cautious. It made her try to guess what I wanted instead of thinking through what she actually understood.

And if you have a kid like Nora, you know the pattern.

They stop taking healthy risks.

They stop trying the hard problem first.

They start asking for reassurance for every step.

They want you to tell them what to do, not because they’re lazy, but because they’re scared to be wrong.

I realized that my correcting was making homework faster in the moment, but it was making her confidence smaller over time.

I didn’t want that trade.

The Shift: From “Fixing” to “Staying With”

So I tried something different, and honestly it felt awkward at first.

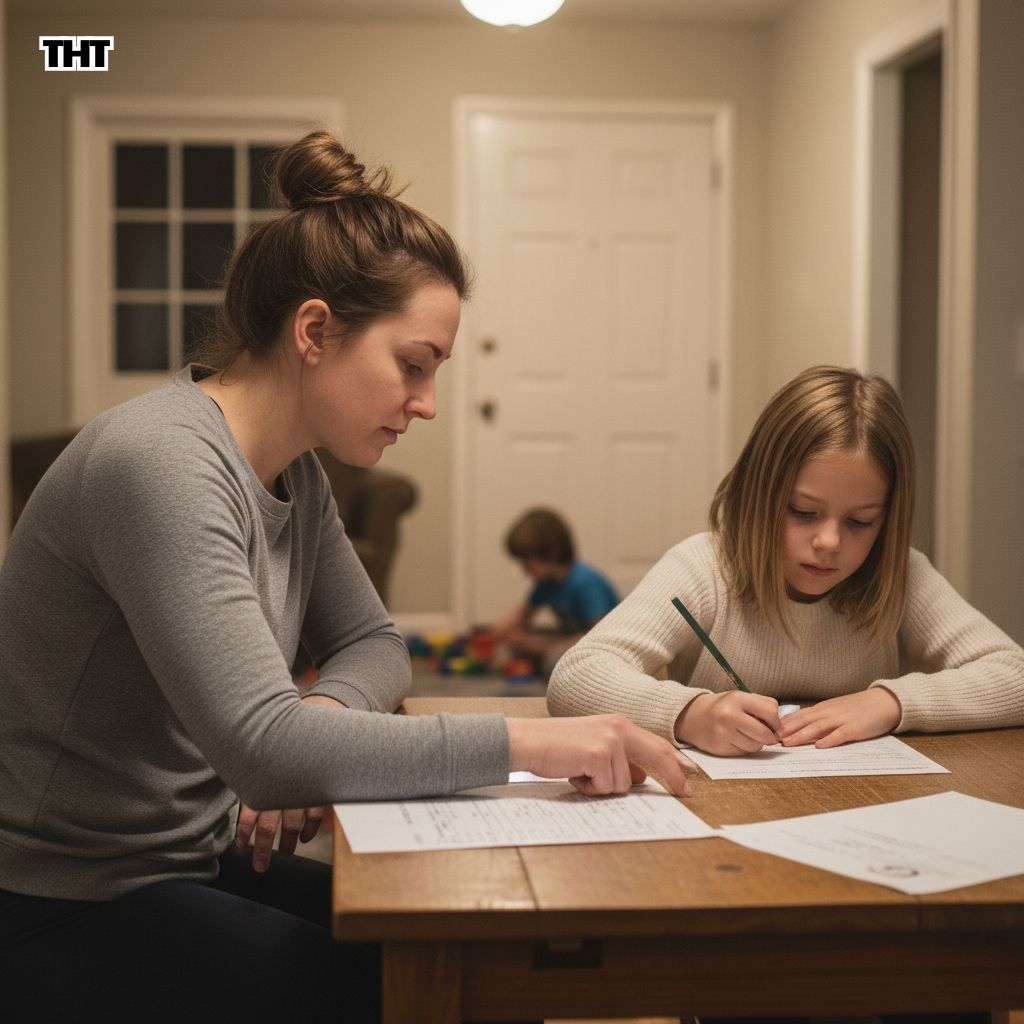

The next day, Nora sat down with her homework again. I made a point to sit beside her, not across from her. This was intentional. Across feels like evaluation. Beside feels like partnership.

She started working, and I watched my brain try to do its usual thing.

She wrote something down that was wrong, and I felt my mouth ready to say, “No, not that.”

Instead, I kept my mouth shut.

I took a breath and asked myself what I actually wanted her to learn.

I wanted her to learn how to think.

I wanted her to learn how to check her work.

I wanted her to learn that being wrong is part of learning, not proof that she isn’t smart.

So I did not correct her.

I stayed beside her and asked questions that helped her stay in her own brain.

“What do you think the question is asking?” I said.

She paused. She reread it.

“What information do we have?” I asked.

She underlined numbers.

“What could we try first?” I asked.

She picked an operation.

Sometimes it was still wrong, but something different happened.

Instead of freezing and erasing furiously, she stayed in it longer. She thought longer. She didn’t immediately look at me like I was the judge.

She was doing the work.

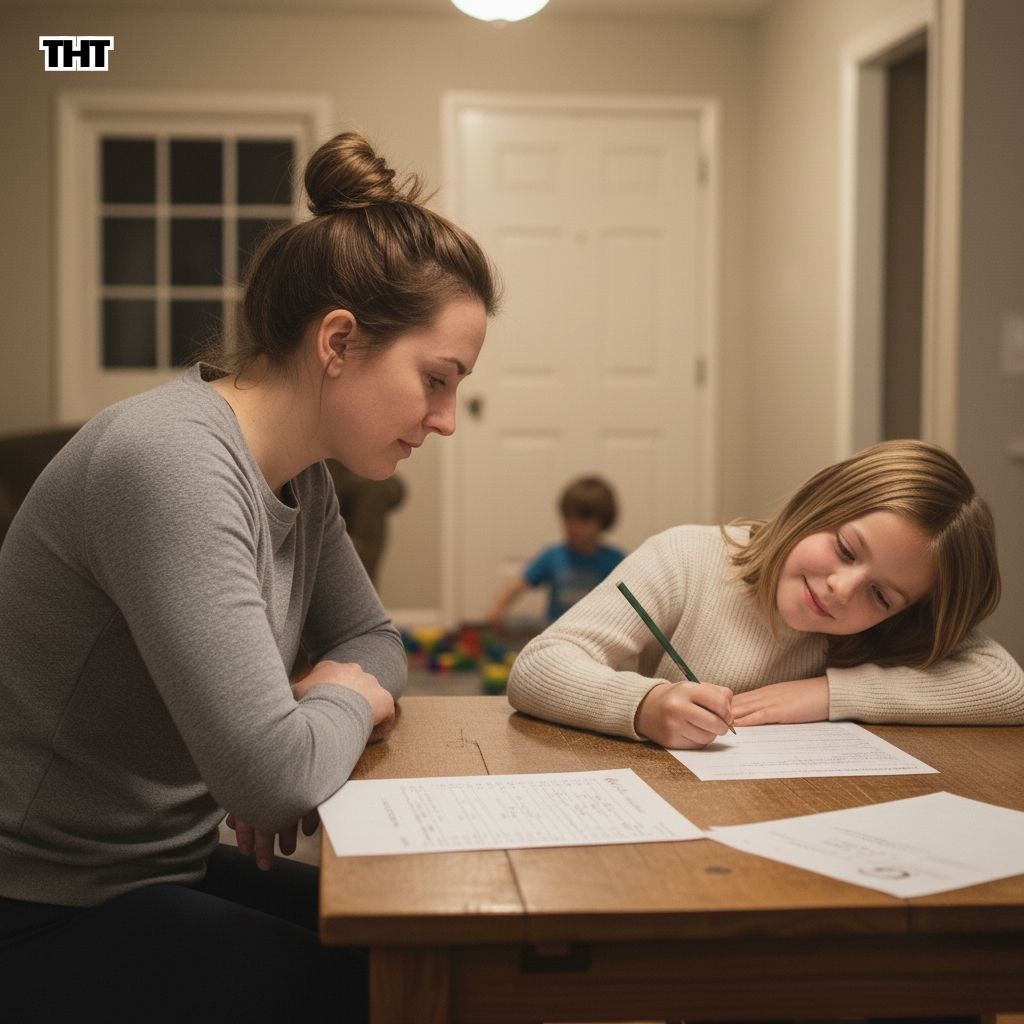

The Night It Worked Better Than I Expected

A week or so into this new approach, we hit a problem that would have absolutely set her off before. It was one of those math questions that takes three steps, and if you mess up step one, you feel like you ruined everything.

Nora stared at it for a long time.

“I don’t know,” she said softly.

In the past, I would have jumped in with an explanation. I could feel the old habit tugging at me, because helping quickly feels good. It feels productive. It also feels like control, and control can be comforting when you’re tired.

Instead, I moved my chair a little closer and said, “Okay. Let’s just start by telling me what you do know.”

She looked up, surprised.

“Well,” she said, “I know it’s talking about how many stickers she has left.”

“Great,” I said. “So we know we’re looking for what’s left. What happened to the stickers in the story?”

Nora read again. She pointed to a sentence. “She gave some away.”

“Okay,” I said. “When you give away, what usually happens to the number?”

Nora frowned, thinking. “It goes down.”

She wrote subtraction.

Then she paused and said, “Wait. But she also got more.”

“Interesting,” I said. “So it went down, and then it went up. What does that mean we might need to do?”

Nora’s eyes lit up, just a little, like the lights coming on in a hallway.

“I think… two steps.”

“Yes,” I said. “And you just figured that out.”

She solved it. Not because I told her the answer, but because I stayed beside her long enough for her brain to do the work.

When she finished, she leaned back and said, very quietly, “I thought I was going to cry.”

Then she laughed, which was such a Nora thing to do, because she can be serious and funny in the same breath when she feels safe.

Here’s the Part I Messed Up, So You Don’t Have To

Here’s the part I messed up, so you don’t have to.

When I first stopped correcting, I went too far in the other direction and became almost annoyingly vague.

Nora would ask, “Is this right?” and I would say, “What do you think?”

That sounds wise, but when your kid is already anxious, it can feel like a dodge. It can feel like you’re refusing to help.

So I adjusted.

Now I do two things.

First, I validate the feeling. “You’re not sure. That’s a normal feeling.”

Then I offer a supportive next step instead of an answer. “Let’s check it together.”

Sometimes we check by rereading the question. Sometimes we check by estimating. Sometimes we check by doing the problem a second way. Sometimes we check by plugging the answer back in.

The key is that we check together without me swooping in like the answer helicopter.

What I Ask Instead of Correcting

I don’t use a script every time, but I do rely on a handful of questions that keep Nora in her own thinking and keep me from turning into the Homework Police.

Here are the ones that work best for us.

“What part feels confusing?”

“What do you notice?”

“What do you already know for sure?”

“What’s the first small step?”

“Can you explain your thinking to me?”

“If we check your answer, how could we do it?”

These questions don’t feel like tests when I say them gently. They feel like I’m sitting with her, not hovering over her.

Why Sitting Beside Her Matters More Than It Sounds

It’s not just posture. It’s not just furniture arrangement. Sitting beside her sends a message.

It says, I’m not evaluating you. I’m with you.

It says, You don’t have to be perfect for me to stay.

It says, You can struggle and I won’t panic.

For Nora, who tends to get stuck in “what if I’m wrong” spirals, that message is everything.

Also, I noticed something else.

When I stopped correcting, I started seeing her strengths more clearly. She is thoughtful. She notices patterns. She can problem-solve when she’s not stressed. She’s creative in the way she approaches questions. Those strengths were always there, but my correcting was crowding them out.

What Changed for Miles, Too

This wasn’t just a Nora shift, even though it started with her.

Miles watches everything. He may look like he’s not paying attention, but he absorbs the mood of the house like a sponge.

When homework stopped being tense, the whole evening felt calmer. Nora was less snappy afterward. I was less snappy. Chris walked into a house that felt lighter.

Miles even started sitting at the table sometimes, building quietly while Nora did homework, which is the closest he gets to “studying” at this age.

And when he asked for help with a simple worksheet, I used the same approach. Instead of correcting his letters mid-stroke, I sat beside him and said, “Let’s do one together, then you try.”

He stayed engaged longer than usual. That’s not a miracle. That’s nervous system safety.

The Practical Hack That Helped Me Stick With It

Here’s a practical hack that made this change easier to maintain.

I made “Homework Tea.”

It’s not fancy. It’s just warm tea for me and warm cocoa or herbal tea for the kids in little mugs. The drink isn’t the point. The ritual is the point.

It signals to all of us that this is slow time, not rushed time. It reminds me to soften my tone. It helps Nora relax her shoulders. It gives Miles something to sip so he’s not constantly interrupting.

You could do it with warm milk, or a snack plate, or a specific lamp you turn on, anything that signals we’re entering a calmer space.

But the ritual helps my brain stop treating homework like something to rush through.

Final Thoughts

I still want Nora to do her work well. I still care about learning. I still step in when she’s truly stuck or when the frustration is tipping into tears.

But now, I’m more careful about how I help.

I don’t correct first. I connect first.

I sit beside her, not across from her.

I ask questions that guide her back to her own thinking.

And when she makes a mistake, I treat it like information, not an emergency.

Homework is not just about math or spelling. In our house, it’s also about learning how to stay with hard things, how to ask for support without giving up, and how to trust your own brain.

The biggest change wasn’t that Nora suddenly loved homework. She still doesn’t love it, and honestly, fair. The biggest change was that she stopped being afraid of it.

And when she looks at a problem now and says, “I don’t know,” she doesn’t sound like she’s collapsing. She sounds like she’s beginning.

Which is exactly what I want.